It wouldn’t be a stretch to think many Canadians share a similar perception of what those working in the nation’s oil and gas industry look like.

But over the last year, the Canadian Energy Centre has profiled many of the women and men who keep the critical sector humming, and preconceptions of those in industry do little justice to its diversity.

Take Prince Azom of Cenovus Energy, one the world’s few experts in solvent technology in the oil sands, a critical advance in reducing water use and greenhouse gas emissions.

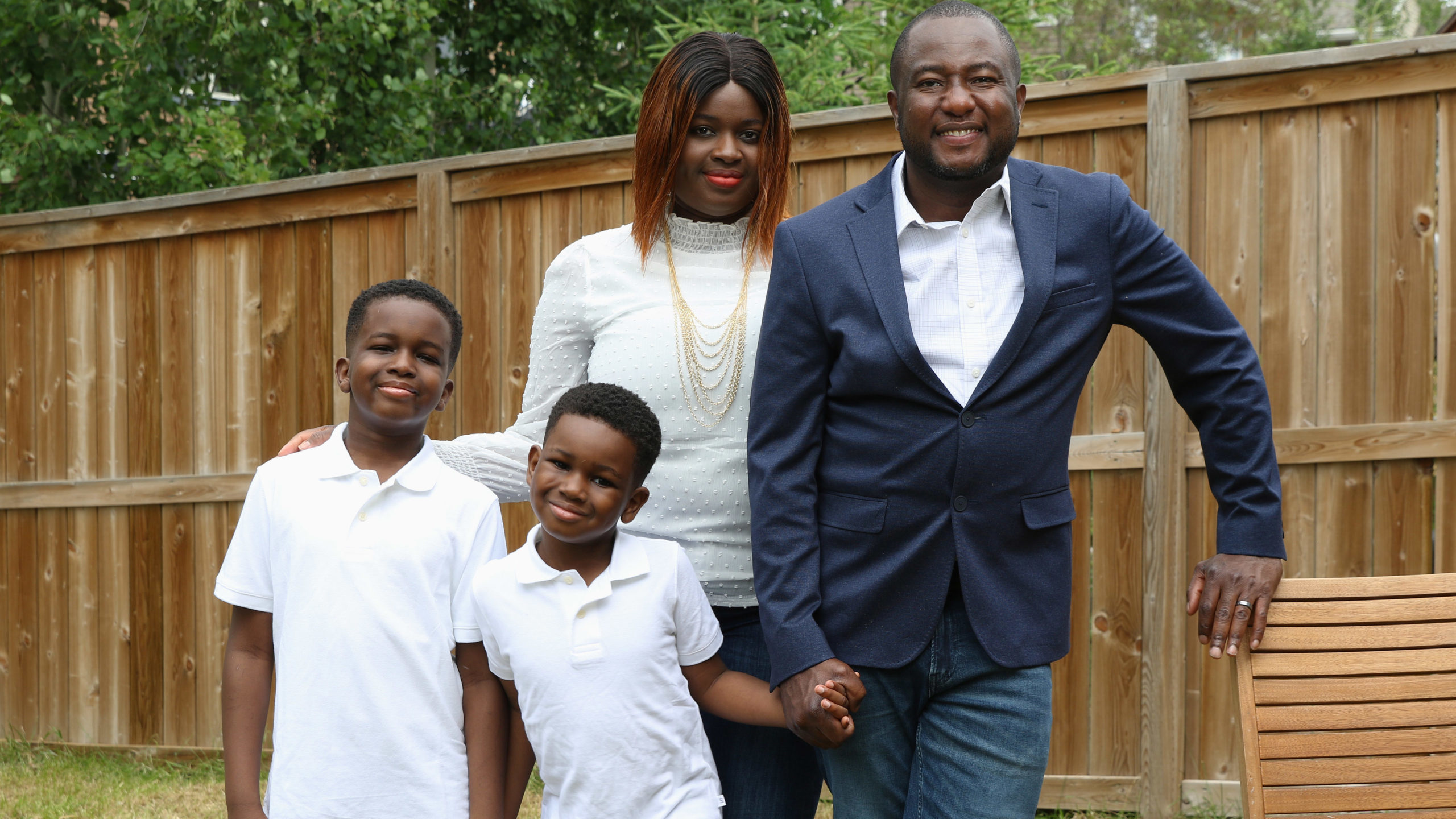

After attaining a degree in chemical engineering in Lagos, the Nigerian native embarked on a global journey that would ultimately bring him and his family to Canada in 2013, where he is now a senior reservoir engineer in the Technology Development group that is finding ways of producing oil using less water and heat, and with lower greenhouse gas emissions.

“My experience in Canada so far has been amazing,” the father of two told the CEC.

“The innovation system here is the best in the world, and the collaboration between companies to improve and reduce the environmental impact of the entire industry doesn’t exist anywhere else that I have seen.”

Azom is one of 28,000 landed immigrants who found employment in the quarrying, mining and oil and gas extraction sector in 2019, according to CEC research. That cohort has mostly grown over the past 15 years, and average weekly earnings for immigrants in the resource sector were found to be 71 per cent higher than the average of all industries in Canada.

The industry also provides lucrative employment for Canadians from coast-to-coast, with Alberta’s energy sector alone providing jobs for nearly 100,000 workers from other provinces in 2016. Those inter-provincial employees were able to earn $57.4 billion between 2002 and 2016, money that would ultimately be returned to their own local economies, from B.C. to the Maritimes.

Andrew Ivany, who lives in St. John’s, Nfld., has spent his entire adult life working months at a time in Alberta’s oil patch so he can return home to spend his summers surrounded by family and friends.

“I moved to Edmonton right out of high school back in 1996 because it was good, reliable work,” says Ivany, who also works construction jobs.

“It’s meant a lot to me. Alberta has provided nothing but open arms for me and opportunity. Newfoundlanders love Alberta – what’s not to love?”

Industry-related jobs are part of a vastly diverse employment ecosystem, and the CEC has only scratched the surface speaking with those employed as avionics engineers, human resources professionals, environmental engineers and more.

Canada’s world-wide leadership in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance has also turned former foes of the oil and gas industry into some of its staunchest supporters.

While attending university in New Brunswick, Heidi McKillop would join her friends in protesting oil and gas fracking before she experienced an awakening about her own connections to those critical resources and how they impacted her everyday life.

“The problem is that it’s so polarizing and these are concepts are very difficult to get people to listen to because they are kind of boring to the average person,” she says.

“We’re so affluent here in Canada; we have this resource and we absolutely take it for granted in every shape and form.”

McKillop’s revelation prompted her in 2018 to produce a self-funded documentary called A Stranded Nation, examining how misconceptions about Canada’s oil and gas industry have hobbled economic opportunities for Canadians while its global rivals have benefited.

Similar to McKillop, Kaella-Marie Earle, now a member of the Canadian Energy Regulator’s inaugural Indigenous Advisory Committee, was no stranger to protesting pipelines and the oil and gas sector.

But she experienced her own personal turning point when she realized she could help play a part improving the industry’s already strong track record of environmental innovation and in working closely with First Nations communities.

“I found myself in an industry that truly cares about listening to Indigenous people, truly cares about changing to address climate change, and is ready to hear from different people on how to do it so everyone benefits,” she says.

And while some are inspired to become advocates, for at least one artist, industry’s efforts to restore ecological balance has become the inspiration for her paintings.

Alberta artist Shannon Carla King, who has worked in oil and gas for over 30 years, paints beautiful landscapes with a twist – they feature oil sands environments that have been reclaimed or constructed by producers to better protect the environment.

“I wanted to create a conversation where people focus on the great things that the oil and gas industry is doing and our country’s high environmental standards,” says King, who saw three of her pieces featured at the Federation Gallery on Vancouver’s Granville Island this October as part of an environmental issues focused-exhibition called CRISIS, which collected donations for the David Suzuki Foundation.

“It may not change their mind, but if I can get them to just pause for one moment and challenge their perspective, that’s a win for me.”