The Trans Mountain project has loaded petroleum on marine vessels off the south coast of B.C. with no spill incidents in nearly 65 years of tanker operations. Now, the expansion of the pipeline and marine terminal brings with it a landmark investment that will improve safety for all users including oil tankers, cargo ships, cruise liners and other vessels.

Increased shipping on the oil pipeline from Edmonton, Alta. to Burnaby, B.C. will increase exports through Trans Mountain’s Westridge Marine Terminal, from 5 to up to 34 tankers per month. But marine shipping experts don’t expect the project’s safe record to change with the additional movements.

“Vancouver sees about 3,000 to 3,500 deep sea vessels a year. So with the TMX, we’re probably looking at about a 10 to 12 per cent increase in traffic for the port,” says Captain Chris Badger, former chief operating officer of the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority.

Badger is one of eight specialists in marine shipping, regulation, risk management and engineering who contributed to a recent report by Resource Works on Trans Mountain oil tanker safety.

“It makes the port of Vancouver a fairly large port in North America, but quite small compared to large global ports,” he says. “Personally, I don’t really see [how] an increase of shipping from say 3,200 to 3,600 would have any material impact on safety.”

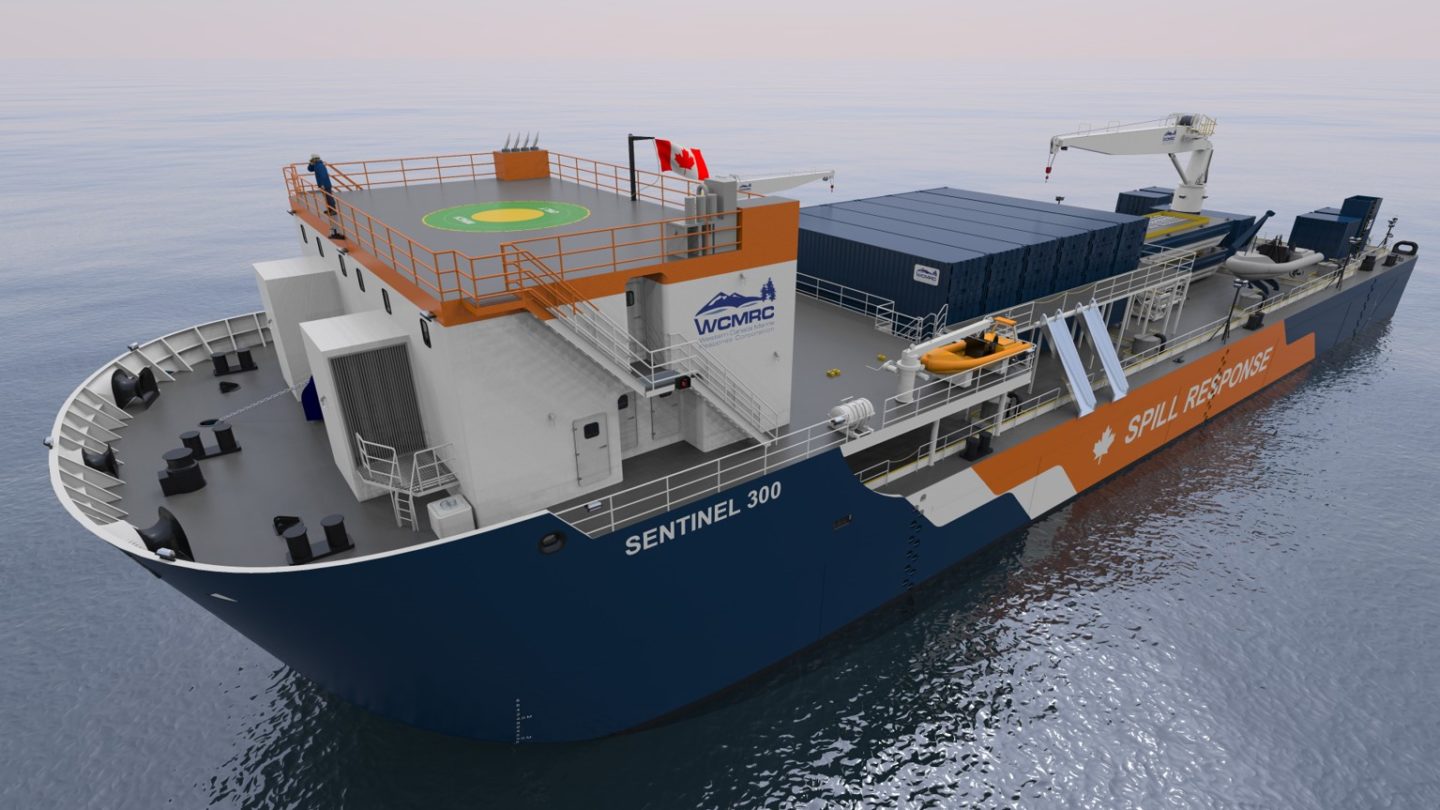

Even still, as part of the expansion Trans Mountain is investing $150 million on the largest-ever expansion of spill response on B.C.’s south coast. The funding goes to Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC), which is responsible for responding to potential marine oil spills along all 27,000 kilometres of B.C.’s coastline. On average, WCMRC responds to about 20 spills each year.

“We compare oil spill response to fighting a forest fire,” says Michael Lowry, WCMRC’s manager of communications.

“In both cases, a lot of things are out of our control, such as weather, size of the spill or fire, and location. One aspect we can control, however, is response time. The quicker we get there, the more we can mitigate the impact, and that is one of the single biggest factors in addressing oil spills.”

Cutting spill response times

Trans Mountain’s investment to expand WCMRC capacity is expected to cut the response time required by Transport Canada to two hours from six in the Port of Vancouver and to six hours from 72 in shipping lanes. When new equipment and response bases are in place, WCMRC will have capacity to clean up a 20,000-tonne spill in 10 days, doubling the existing standard.

“To achieve these goals, we are building six new spill response bases along B.C.’s South Coast, including two 24/7 on-water bases,” says Lowry. “As well, we are doubling the size of our response vessel fleet from 44 to 88, and adding 135 full-time positions, primarily for response personnel.”

While the quantity of new vessels is impressive, the quality is also worth noting, such as the three purpose-built coastal response vehicles. These craft are long, wide, slow and steady, and made specifically to address the challenging West Coast weather.

“We are also bringing in an offshore supply vessel that is designed to serve offshore oil platforms,” Lowry says. “These vessels hold a lot of oil and have a large deck for equipment, and have proven very useful in spill response. Because there is no offshore industry on the West Coast, we haven’t had access to such vessels, so this will be a big change.”

Significant progress is being made on the new marine safety enhancements. To date, 10 new response vessels have been delivered and 85 additional employees hired, with construction underway on all six new bases. Lowry is confident that the work will be completed by the end of 2022, when the Trans Mountain expansion is expected to go into service.

Layers of safety protocols protect B.C.’s south coast

There are layers of safety protocols regarding oil tankers on B.C.’s south coast, says Resource Works executive director Stewart Muir.

“When a tanker moves from Burnaby with oil bound for China or Los Angeles, it has a skilled crew to guide it. The ship is under the control of a Canadian coastal pilot who watches everything onboard and navigates the tanker out past Victoria before turning the vessel back over to its captain,” he says.

Alongside the tanker, there are three modern, powerful tugboats designed especially for the Port of Vancouver, he says. These nimble craft can rotate 360 degrees and steer the vessel if it loses rudder control, thereby preventing a collision.

“In addition, there are systems and protocols watching over the vessel, such as the 24/7 marine operations centre atop a building in downtown Vancouver that acts like an air traffic control centre.”

Double hull tankers

Another layer of protection is the double hull design found in all modern oil tanker ships – a requirement following the Exxon Valdez oil spill off the coast of Alaska 32 years ago. Muir says Exxon Valdez transformed shipping safety for oil tankers.

“One major change was the move to a double hull structure that greatly reduces the risk of pollution. Today’s tankers have up to 18 cargo compartments,” Muir says.

“Imagine a bathtub filled with a bunch of jerry cans of gasoline. If someone takes a sledgehammer to the tub, they might crack the tub itself, but the liquid is still secure inside those containers…Many people think that if a tanker springs a leak it’s toast, but the true story is different.”