Russia’s largest oil company doesn’t seem to be buying into the flawed peak oil narrative that has taken over headlines around the world. Instead, Rosneft is setting up to fill the void left by companies like BP and Royal Dutch Shell as they pledge to reduce fossil fuel investment despite expectations for continued growth in oil demand.

It’s a void that Canada, despite its vast resources and high environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards, is challenged to fill due to a lack of pipeline access and environmental pressures.

This September, a senior executive with Rosneft, which is majority owned by the Russian government, was quoted in the Financial Times warning that actions like those by BP and Shell are creating an “existential crisis” for global oil supplies that will lead to higher prices and shortages in the future.

“Someone will need to step in … someone will need to take that responsibility,” Didier Casimiro told the Financial Times Commodities Global Summit.

In late November, Rosneft announced it is starting development of a massive oil project the size of which eclipses anything seen in Canada.

It’s called Vostok Oil, and according to Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin, it will create “a new oil and gas province” in the country’s north.

Rosneft says that developing the Vostok project will require 400,000 workers and create 15 new “industry towns.” The project will build 800 kilometres of new pipelines and require 100 drilling units.

By 2024, it is expected to deliver about 600,000 barrels per day to tankers on Russia’s Northern Sea Route. With completion of the first phase, that will increase to approximately one million barrels per day, and to two million barrels per day with completion of the second phase. The full cost is expected to be as high as $170 billion.

That Russia would proceed with such a giant project now is not surprising to Tim Pickering, president of Calgary-based Auspice Capital Advisors.

“The large oil producers of the world are going to keep doing exactly what they have been doing. If you look at Russia and you look at Saudi Arabia and also the United States, they do what’s right for the economics and security of their nations and don’t beat anybody else’s drum, and [in Canada] we continuously do,” Pickering says.

Flawed headlines

Eric Nuttall, partner with Toronto-based Ninepoint Partners, says that the recent “pile-on” of negative news headlines would lead one to believe that the end is nigh for oil, while the hype around renewables is the strongest he has ever seen.

“There is unquestionably a negative bias towards the energy sector both in Canada and in the global mainstream media,” Nuttall said on a recent Ninepoint Partners podcast. He says this is contributing to lower stock prices for companies like Royal Dutch Shell and BP, which is likely driving their announced strategic shifts away from fossil fuels.

“These executives are under enormous pressure to do something differently to try to get their stocks to start working,” Nuttall says. “You’re seeing the energy companies react to the negative pile-on from headlines that have certain flaws of logic.”

The biggest flaw of logic that Nuttall sees is about energy use and population growth. According to United Nations forecasts, the world’s population is expected to grow by 2 billion people by 2050, reaching 9.7 billion, driven primarily by growth in India.

“Not only is the world growing in size and population, it’s growing in areas where people are suffering from energy scarcity, where we see the world through the lens of energy abundance,” Nuttall says.

“These 2 billion people are not in Canada, [and] not in the United States. It’s in countries where they yearn for our standard of living and our quality of living, and our standard of living is incredibly energy intensive.”

The International Energy Agency forecasts that India’s oil demand will increase from 5 million barrels per day in 2019 to 8.7 million barrels per day in 2040. Overall, under the current trajectory the IEA forecasts that global oil demand will increase from 97.9 million barrels per day in 2019 to 104.1 million barrels per day over the same period.

“Do we need alternatives or renewable energy for the future? We absolutely do, but at the same time we also need hydrocarbons. We need oil and we need natural gas,” Nuttall says.

“While we’re going to see declines likely in developed countries, let’s focus on where it’s growing because the growth is way more meaningful than the declines.”

Seeing through the hype

The peak oil narrative is also flawed because it is carried to a large extent by energy illiteracy, say both Pickering and Nuttall. For example, the impact of electric vehicles (EVs) on overall oil demand is often misunderstood.

“There’s no doubt that renewables and electric vehicles and these things are happening, but EVs have such a tiny impact, it’s almost irrelevant,” Pickering says.

“Oil isn’t just for consumer driving. Global transportation is going to be a lot harder to go EV: planes, trains, shipping, [and] trucking are going to take a lot of time. These are the big consumers, not to mention everything else we use oil for.”

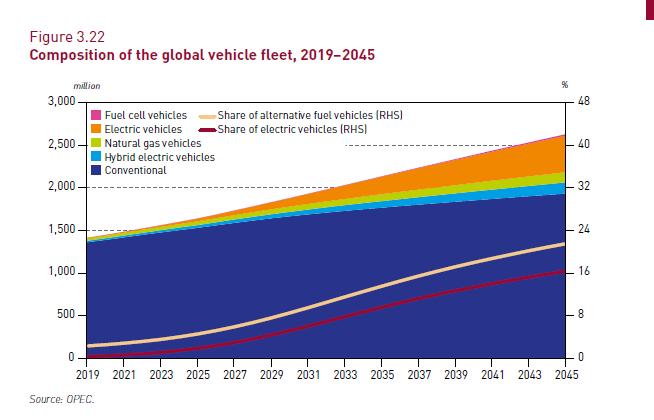

Nuttall points to OPEC’s latest forecast, which predicts passenger cars and commercial vehicles globally will increase from 1.4 billion currently to 2.6 billion by 2045. Of that 2.6 billion, approximately 430 million – or about 16 per cent of the total – will be EVs.

Wood Mackenzie’s current forecast is that there will be 300 million passenger EVs by 2040, displacing the need for about 5 million barrels per of oil per day, or about 5 per cent of current demand.

Nuttall also questions the impact that future hydrogen development, as outlined by BP’s forecast scenarios, will have on global oil demand.

“Using BP’s own newly-woke math, under a rapid adoption scenario they have that by 2050 hydrogen is going to displace seven exajoules of oil demand, which sounds like a really, really big number. [But] how big is the oil market in exajoules? It’s 193 exajoules. Their justification for pivoting away from hydrocarbons, hydrogen, could maybe displace 4 per cent of oil demand by 2050,” he says.

“You can look through the hype and you can see that it is clear and obvious that the demand for hydrocarbons, the demand for natural gas as a bridge fuel [and] the demand for oil will be with us for many, many, many decades to come.”

While it’s common today to talk about peak oil demand and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on oil use around the world, Nuttall says “what’s way more impactful” is happening on the supply side.

“The fear of peak demand is leading us to the reality of peak supply,” he says.

Canada missing out

The Rosneft project is further evidence that Canada is missing out on a huge opportunity to supply responsibly produced oil to meet the world’s hungry demand, Pickering says.

Canada ranks number one in terms of environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance compared to the world’s top oil and gas reserve holders, according to BMO Capital Markets. Since 2000, Canada’s oil and gas sector has paid more than $493 billion in taxes and royalties to federal, provincial and municipal governments, according to CEC research.

“At the end of the day, Canada is a resource-based economy. The resource industry has made this country and continues to be the largest contributor to GDP,” Pickering says.

“We as a society have this resource. We need to extract it responsibly and get the fair price for it.”