The resilience of Canada’s oil sands is on display despite the sector going through the greatest oil shock in history, according to energy analysts.

Full-year financial and production results are now in for 2020, and they show that oil sands producers fared better than their biggest competitors, in the United States.

“Alberta’s oil sands survived it. In fact, they performed better and rebounded faster than their American counterparts in the tight oil areas,” said Peter Tertzakian, deputy director of the ARC Energy Research Institute, in a Mar. 9 podcast.

“Whatever you think of the oil sands region, events of the past year should dispel any notion that it’s the world’s most vulnerable, high-cost producer,” he wrote in an associated blog post.

The pandemic has shown how integral oil is to power the world, according to Joseph McMonigle, secretary general of the International Energy Forum (IEF), which represents energy ministers from 70 producing and consuming nations including Canada, the United States, China, India, Norway, and Saudi Arabia.

“In 2020 we saw oil demand fall by 10 million barrels per day, but as you will see, 2021 forecasts show a rebound in demand of about 5 to 6 million barrels per day,” McMonigle said during a February joint virtual session with OPEC and the International Energy Agency.

“Certainly the impact to demand was profound and unprecedented, the biggest demand shock in history, but it is important to note that 90 per cent of demand remained intact, demonstrating oil’s resiliency and necessity to fuel the world economy.”

More than light-duty vehicles

Jackie Forrest, executive director of the ARC Energy Research Institute, estimates that at the height of pandemic lockdowns in April 2020 approximately one-third of the world’s vehicles were off the road and up to 95 per cent of airplanes out of the sky. At that height of the immobilization, global oil demand dropped by just 20 per cent.

“It is shocking, because I think a lot of people didn’t realize that light-duty vehicles are not the only thing that consumes oil. We still continued to want to eat and move goods around, and a lot of shipping still happened,” Forrest said. “That level of lockdown didn’t reduce oil demand maybe as much as people thought.”

In addition to transportation fuel, oil is used to make countless plastic and synthetic products from clothing, computers, cell phones, car components and furniture to medical equipment, plexiglass, hand sanitizer, carpets, toys, and beauty products.

Forrest says that while the impact of the lockdown on oil demand may have been less than expected, it nevertheless had drastic impacts for oil and gas producers and their business supply chains.

Production losses

Oil sands companies were some of the first globally to shut in production as the lockdown began, Forrest says.

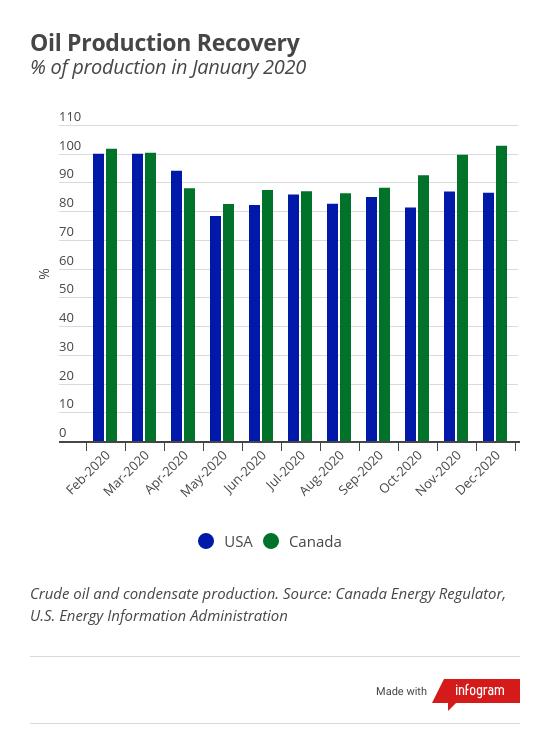

Overall Canadian oil production decreased by more than 850,000 barrels per day between March and May 2020, according to the Canada Energy Regulator. However, this was temporary. Companies started to bring production back online by June, steadily increasing to reach a record 4.9 million barrels per day in December.

In the United States – Canada’s biggest oil competitor and customer – companies shut in production too. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, U.S. oil production dropped to 9.6 million barrels per in May from 12.3 million barrels per day in March. As of December, production remained stuck near 10 million barrels per day.

Oil sands comeback

A key difference between U.S. tight oil and Canadian oil sands is the “decline rate,” or how much drilling is needed to keep production at a certain level.

Oil sands projects require large upfront spending, but because of geology, once they are up and running have lower rates of decline, resulting in relatively low spending after the initial capital cost.

With different geology, U.S. tight oil production is less costly to start up but has high rates of decline, requiring a constant churn of new drilling to keep rates steady.

The end result is that when oil sands producers shut-in production, they can dial it back up relatively easily compared to their competitors.

“People were thinking at this time last year or 11 months ago that the oil sands were going to be the ones to have the most damage done to them, but no, because they have a flatter base decline rate,” says Phil Skolnick, analyst with Eight Capital.

‘We need new oil projects’

The world “may be walking into a supply crunch in a few years’ time” due to underinvestment in oil projects, according to Tom Ellacott, a senior vice-president with energy consultants Wood Mackenzie.

Global oil demand has recovered to 94 per cent of its level pre-COVID, or 95.89 million barrels per day as of February 2021, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). The EIA forecasts that by the end of 2021, oil demand will have reached 98 per cent of levels pre-COVID, and it will continue to rise to exceed pre-pandemic levels by December 2022.

This would represent the largest two-year global oil demand increase on record since 1950, according to the American Petroleum Institute, which is warning that a shortage could be on the way as investment in supply lags.

“The message is simple: we need new oil projects,” Helle Kristoffersen, president of strategy and innovation with France-based Total SA, told the company’s fourth-quarter investor call. “That’s true even if you take a very cautious view on short-term demand recovery and on future demand levels.”

Total projects that the world could be short the oil it needs by 10 million barrels per day in 2025.

“That’s a massive shortfall of supply to cover in just a very few number of years,” Kristoffersen said.

More reliance on OPEC+

While free-market oil companies focus on returning cash to investors and for some transitioning spending to renewable energy sources, state-owned oil companies like those in the OPEC+ group are more than willing to take up their market share.

The CEO of Russia’s Rosneft reported to president Vladimir Putin in February that the state-controlled oil company is launching new oil projects to meet global demand as existing fields decline and other international oil companies transition to green energy.

“By developing these new fields, we will try to satisfy the deficit that may arise in the market,” he said.

TMX to make Canadian projects ‘extremely competitive’

Right now, Canada has limited access to deliver its own oil to meet the rising global demand. That will change once the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion is put into service, which is expected by the end of 2022. Once the new pipeline is up and running, oil sands projects will become “extremely competitive,” Skolnick says.

He says with TMX online, “you’re going to see not just resiliency but upside for Canadian oil because it is that direct gateway to Asia. That really actually is a re-rate for the competitiveness of Canadian oil sands.”