To sign up to receive the latest Canadian Energy Centre research to your inbox email: research@canadianenergycentre.ca

Download the PDF here

Download the charts here

This Fact Sheet analyzes the upstream oil and gas industry’s record on flaring and venting of gases in Canada relative to other countries. Flaring and venting, while technical in nature, is relevant because both are a source of greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs). For example, in 2019, 150 billion cubic metres (bcm) of flared gases were emitted worldwide, or just under 285 megatonnes of CO2 equivalent. Canada is a major producer of oil and natural gas with the third-largest proven reserves of crude oil, the 17th largest reserves of natural gas, and the fourth-largest producer of both commodities, and so contributes to flaring and venting.

Background

Flaring and venting are two ways in which an oil or natural gas producer can dispose of waste gases. (Venting is the intentional controlled release of un-combusted gases directly to the atmosphere, and flaring is a disposal by combustion of natural gas or gas derived from petroleum.¹) As Matthew R. Johnson and Adam R. Coderre noted in their 2012 paper on the subject, flaring in the petroleum industry generally falls within three broad categories:

- Emergency flaring (large, unplanned, and very shortduration releases, typically at larger downstream facilities or off-shore platforms);

- Process flaring (intermittent large or small releases that may last for a few hours or a few days, as occurs in the upstream industry during well-test flaring to assess the size of a reservoir or at a downstream plant during a planned process blowdown); and

- Production flaring (which may occur continuously for years as the resource, oil, is being produced).

1. Many provinces regulate flaring and venting including Alberta (Directive 060) British Columbia (Flaring and Venting Reduction Guideline), and Saskatchewan (S-10 and S-20). Newfoundland & Labrador also has regulations that govern offshore flaring.

To track GHGs from flaring and venting, Environment Canada defines such emissions as:

- Fugitive emissions: Releases from venting, flaring, or leakage of gases from fossil fuel production and processing; iron and steel coke oven batteries; CO2 capture, transport, injection, and storage infrastructure.

- Flaring emissions: Controlled releases of gases from industrial activities from the combustion of a gas or liquid stream produced at a facility, the purpose of which is not to produce useful heat or work. This includes releases from waste petroleum incineration, hazardous emission prevention systems (in pilot or active mode), well testing, natural gas gathering systems, natural gas processing plant operations, crude oil production, pipeline operations, petroleum refining, chemical fertilizer production, and steel production.

- Venting emissions: Controlled releases of a process or waste gas, including releases of CO2 associated with carbon capture, transport, injection, and storage; from hydrogen production associated with fossil fuel production and processing; of casing gas; of gases associated with a liquid or a solution gas; of treater, stabilizer or dehydrator off-gas; of blanket gases; from pneumatic devices that use natural gas as a driver; from compressor start-ups, pipelines, and other blowdowns; and from metering and regulation station control loops.

Flaring comparisons

This Fact Sheet uses World Bank data to provide international comparisons of flaring only (given the limited international data on venting). It also draws on US Energy Information Administration (IEA) data to compare flaring in major petroleum- (and other liquid-) producing countries.

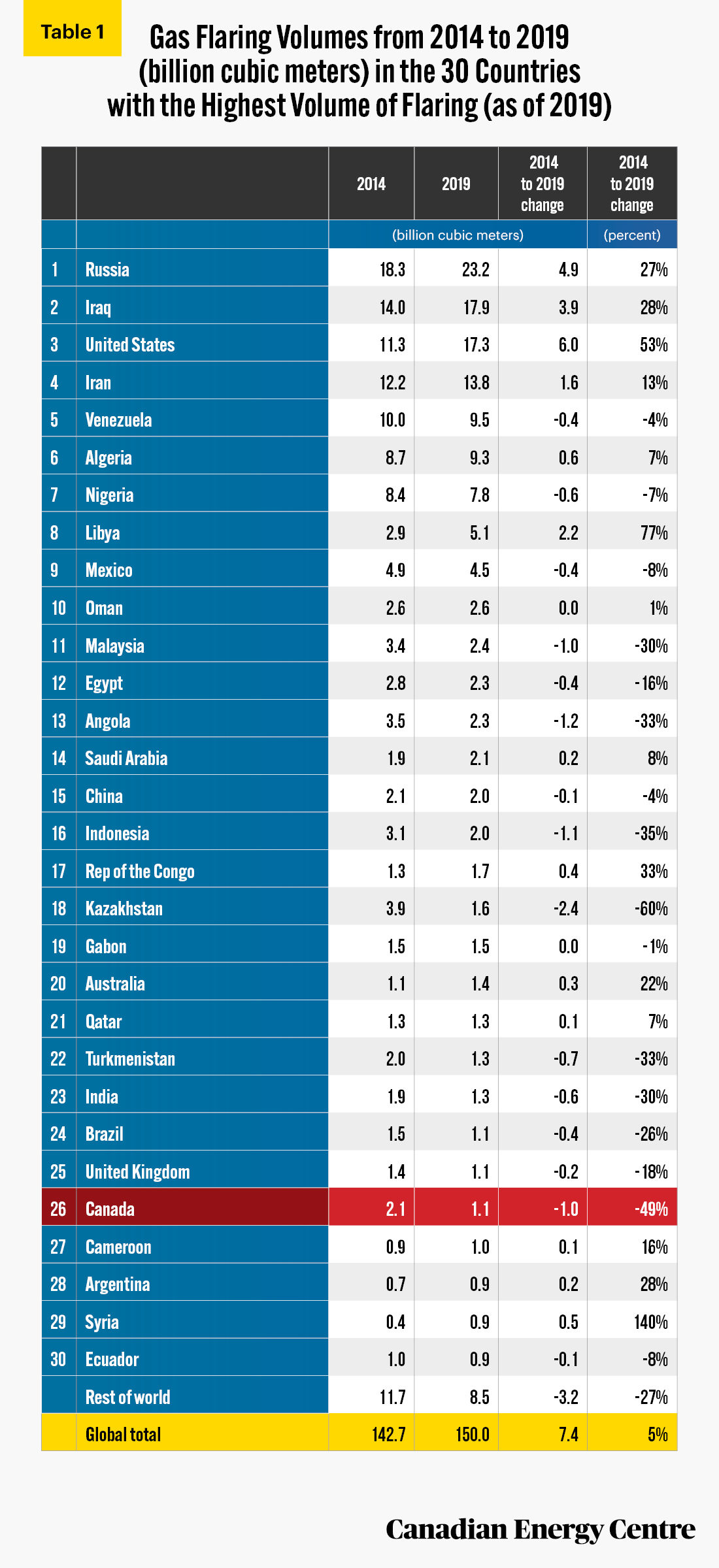

Table 1 shows gas flaring volumes in 2014 and 2019. In absolute terms, Russia recorded more flaring than any other country at 23.2 billion cubic metres (bcm) in 2019, slightly higher by nearly five bcm, or 27 per cent higher, than in 2014. The five countries that were the top GHG emitters through flaring (Russia, Iraq, the US, Iran, and Venezuela) accounted for 54 per cent of global gas flaring in 2019.

At 1.1 bcm, Canada was the fifth lowest flarer in 2019 (in 26th spot out of 30 countries surveyed); it recorded a decrease in flaring emissions of 1.0 bcm from the 2014 level of 2.1 bcm, a 49 per cent drop. Between 2018 and 2019, Canada decreased its flaring volume by 20 per cent from 1.3 bcm to 1.1 bcm, and thus in 2019 Canada’s share of global gas flaring was just 0.7 per cent, despite it being the world’s fifth largest producer of oil and natural gas.

Source: World Bank.

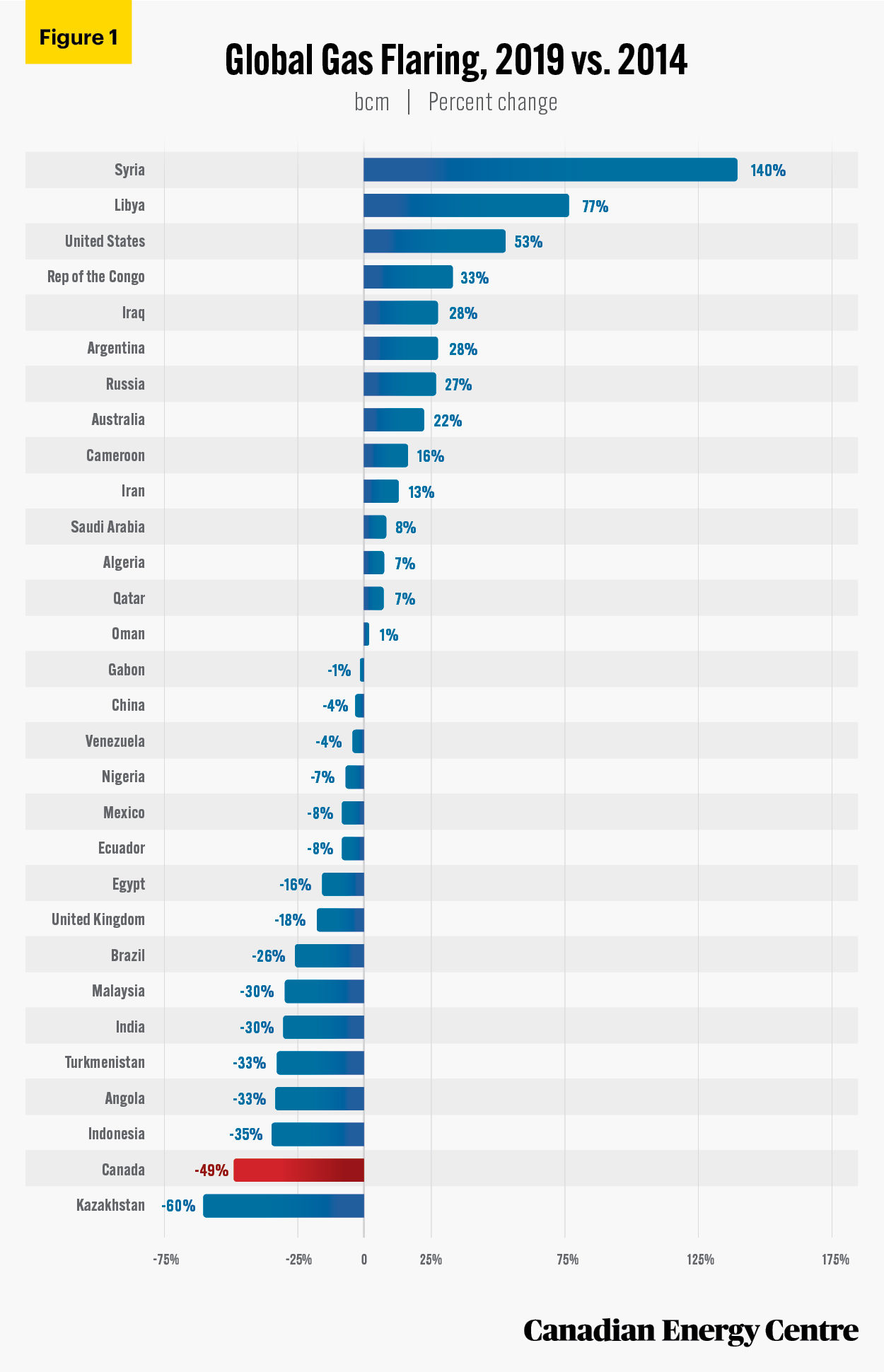

Fourteen countries flared more in 2019 than in 2014; 16 countries flared less

Figure 1 also shows the change in flaring volumes. In total, 14 countries flared more in 2019 compared with 2014, while 16 countries flared less.

- The five countries that showed the greatest increase in flaring were Syria (140%) Libya (77%), the US (53%), Congo (33%), and Iraq at 28% more in 2019 relative to 2014.

- The five countries that showed the greatest decrease in flaring were Kazakhstan (-60%), Canada (-49%), Indonesia (-35%), Angola (-33%), and Turkmenistan (-33%).

Source: World Bank.

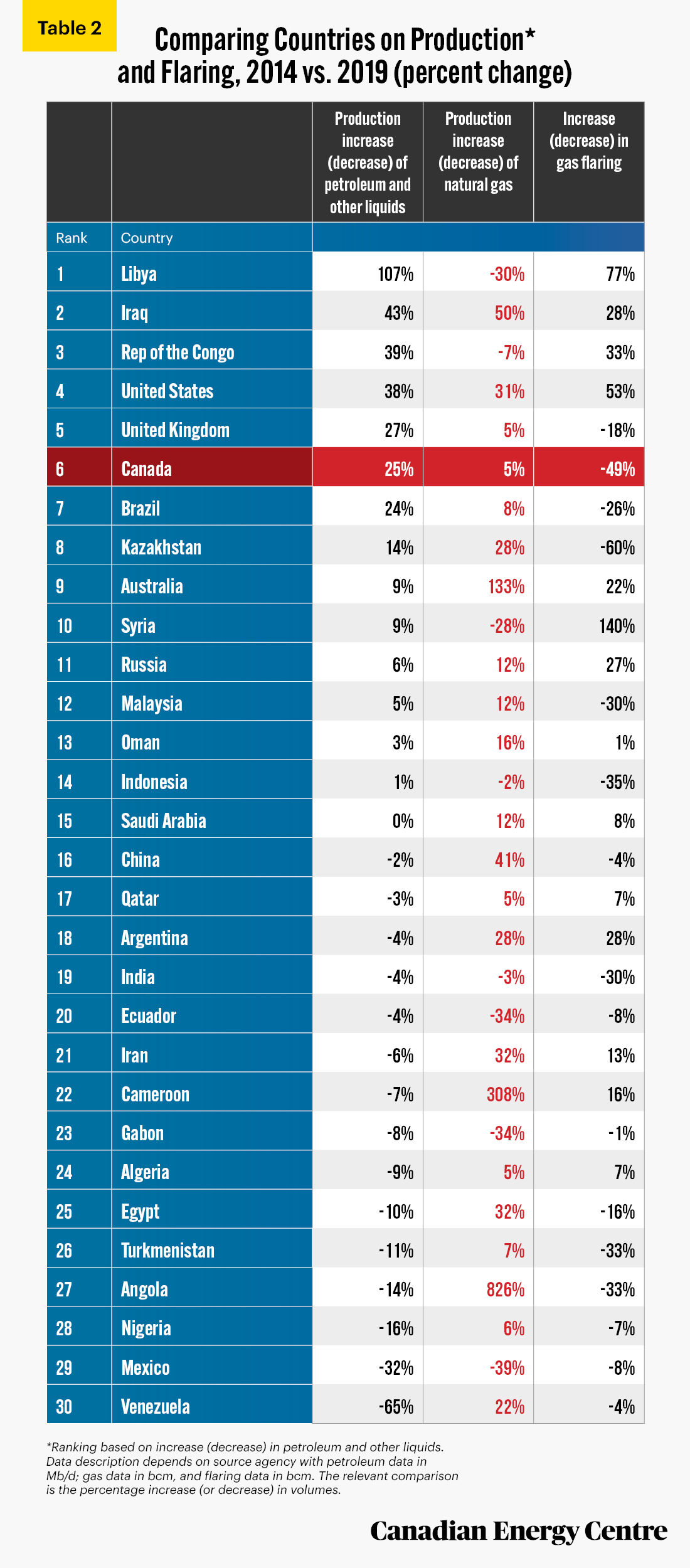

Comparing flaring to increased production

- The decreases in flaring for Canada shown in Table 1 and Figure 1 understate the magnitude of the decline between 2014 and 2019. That is because Canada’s production of petroleum and other liquids has increased by 25 per cent, with natural gas production up 5 per cent in that period, all while decreasing flaring by 49 per cent (see Table 2).2

- Canada compares favourably with the United States, which increased production of petroleum and other liquids by 38 per cent, and increased gas production by 31 per cent, but, unlike Canada, increased flaring by 53 per cent.

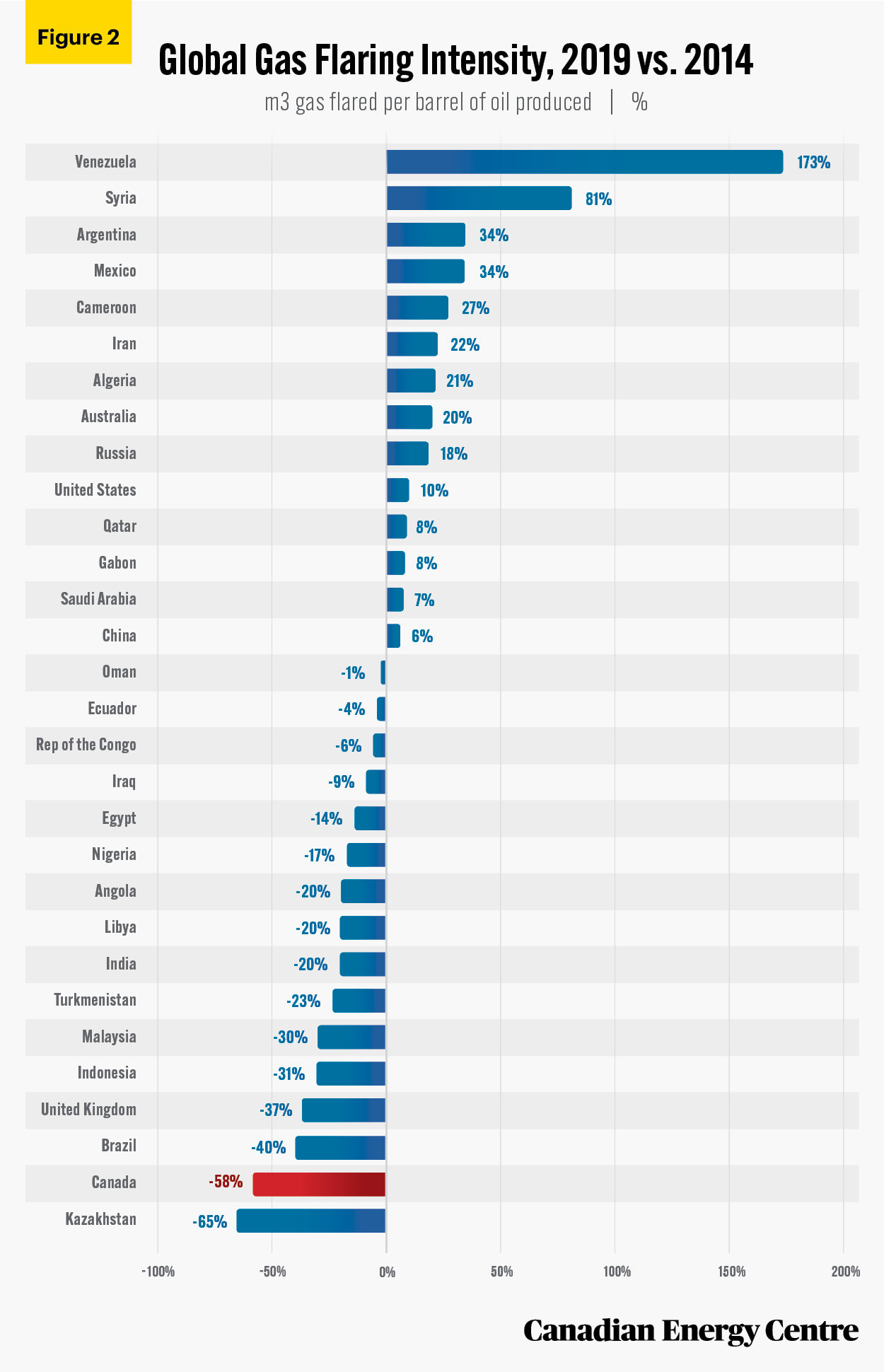

To fully grasp how much more efficient Canada has been in reducing flaring, Figure 2 compares both flaring and production. In Canada, the gas flaring intensity (gas flared per unit of oil production) declined by 58 per cent between 2014 and 2019. Venezuela, which produces heavy crude oil similar to Canada’s, saw flaring increase by 173 per cent (see figure 2). Only Kazakhstan, which recorded a perbarrel reduction in flaring of 65 per cent between 2014 and 2019, showed a decline deeper than Canada’s 58 per cent reduction.

2. As per the US Energy Information Administration data sources, this measurement includes the production of crude oil (including lease condensate), natural gas plant liquids, and other liquids. It also includes refinery processing gain for volume. Natural gas production numbers exclude non-hydrocarbon gases for all countries and include only dry natural gas production.

Sources: World Bank, US Energy Information Administration.

Source: World Bank.

The takeaway

Global gas flaring and venting contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. Canada is an example of a country that produces petroleum and other liquids but that has also significantly reduced flaring, not only in absolute terms but also when compared with increased production volumes.

Notes

This CEC Fact Sheet was compiled by Ven Venkatachalam and Mark Milke at the Canadian Energy Centre: www.canadianenergycentre.ca. All percentages in this report are calculated from the original data, which can run to multiple decimal points. They are not calculated using the rounded figures that may appear in charts and in the text, which are more reader friendly. Thus, calculations made from the rounded figures (and not the more precise source data) will differ from the more statistically precise percentages we arrive at using source data. The authors and the Canadian Energy Centre would like to thank and acknowledge the assistance of Dennis Sundgaard and Philip Cross in reviewing the original 2020 version of this Fact Sheet. Image credit: Dietmar Wiedemann from Pixabay.com.

References (All links live and updated as of March 30, 2021)

Alberta Energy Regulator (2020), Directive 060 <https://bit.ly/3ff22KQ>; BC Oil and Gas Commission (2018), Flaring and Venting Reduction Guideline <https://bit.ly/3frjDfJ>; Saskatchewan Energy and Resources (2010), S-10 and S-20 <https://bit.ly/2BY68Wg>; Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board (2007), Offshore Newfoundland and Labrador Gas Flaring Reduction <https://bit.ly/30zqaAC>; Environment and Climate Change Canada (2020), Technical Guidance on Reporting Greenhouse Gas Emissions/Facility Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program. 2020 data <https://bit.ly/31gfOVh>; Johnson, Matthew R. and Adam R. Coderre (2012), Compositions and Greenhouse Gas Emission Factors of Flared and Vented Gas in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 62: 9: 992-1002. <https://bit.ly/3cJRqPd>; Natural Resources Canada (undated a), Crude Oil Facts <https://bit.ly/3dSAzen>; Natural Resources Canada (undated b), Natural Gas Facts <https://bit.ly/2XN7kEe>; US Energy Information Administration (undated), Petroleum and Other Liquids and Natural gas <https://bit.ly/3rmObVk>; World Bank (undated), Gas flaring volumes 2014-2018 <https://bit.ly/3clVhVN>.

Creative Commons Copyright

Research and data from the Canadian Energy Centre (CEC) is available for public usage under creative commons copyright terms with attribution to the CEC. Attribution and specific restrictions on usage including non-commercial use only and no changes to material should follow guidelines enunciated by Creative Commons here: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs CC BY-NC-ND.