Progress is being made to solve one of the oil sands industry’s highest profile environmental challenges. Thanks to years of companies working together and more than $10 billion of combined sector investment, the future outlook for reduction of oil sands tailings is looking brighter.

A “notable acceleration” in the application of new technologies to treat tailings from oil sands mining is starting to pay off, BMO Capital Markets analyst Jared Dziuba wrote in an investment report earlier this year.

It’s a critical step forward for what he described as an issue “at the centre of the global scrutiny and tainted image of [the] oil sands.”

Major strides have been made by the two largest mining producers, with one reducing new project tailings by half and the other reducing its total operated tailings footprint altogether. Meanwhile, producers on the whole since 2015 have been able to keep tailings inventories lower than expectations, despite increasing oil production.

Dziuba said that based on performance trends and R&D momentum, BMO believes that tailings management will be an important and exciting area to keep an eye on.

“It could act as a catalyst for the sector to vastly improve its image on the global stage,” he said.

Oil sands tailings

Tailings are a consideration in mining operations around the world, created during the extraction process that separates the target valuable product from other material.

The extraction process that unlocked Alberta’s vast oil sands resources to commercial development in the late 1960s is based on hot water. The hot water is used to separate sand and clay from bitumen, which is then treated and sold as oil. This leaves behind a mix of water, sand, clay and residual bitumen that is stored in engineered basins known as “tailings ponds.” These facilities enable the water to be fed back into the system. In 2018, for example, 75 per cent of the water used by oil sands mining producers was recycled using this process.

But decades of operations, increasing oil sands production, technological challenges and the regulatory requirement to store untreated process-affected water have contributed to a large accumulation of tailings in Alberta. Since the introduction of new tailings regulations in 2009 and their continued evolution, producers have heavily ramped up their R&D efforts.

The Alberta Energy Regulator’s current rules for oil sands tailings include a mandate that all fluid tailings must reach “ready to reclaim” status 10 years after the end of a mine’s life.

Investment and collaboration

Tailings are one of four priority areas for Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance (COSIA), a collaboration of the largest producers that exists to accelerate environmental performance improvement. In fact, collaboration on tailings existed before the launch of COSIA in 2012, through the Oil Sands Tailings Consortium.

COSIA chief executive Wes Jickling says operators “are aggressively working on innovative, sustainable approaches to reducing tailings volumes, accelerating tailings reclamation time, increasing water recycling and reducing GHG emissions.”

“Collaboration is driving significant progress through COSIA; oil sands producers, universities, government agencies and research institutes are bringing together shared experience, expertise and best practices to drive innovation,” he said, adding that more than 189 tailings technology and research projects have been or are being advanced through collaboration.

“Industry has invested more than $10 billion into tailings management and the implementation of innovative tailings treatment technology.”

According to BMO’s analysis, the volume of fluid tailings being treated by the various approved technologies has grown substantially, from approximately 60 million cubic metres in 2016 to over 160 million cubic metres in 2018.

“We believe that this trend has been at least partly influenced by regulatory pressures, but also motivated by a drive to revive the sector’s image and lower costs,” Dziuba said.

Work paying off

Suncor Energy hit the first major milestone for oil sands tailings in 2010 when it became the first operator to reclaim a tailings pond to a solid surface. Tailings Pond One, which operated from 1967 to 1997, became Wapisiw Lookout, a 220-hectare area that is being developed into a mixed wood forest and small wetland.

Suncor achieved the milestone using a portfolio of technologies it calls tailings reduction operations (TRO), which BMO said is also responsible for the trend of success it is currently on.

“The company has managed to actually decrease net fluid tailings at its Base Mine despite considerable expansion in production directly as a result of TRO innovations,” Dziuba wrote.

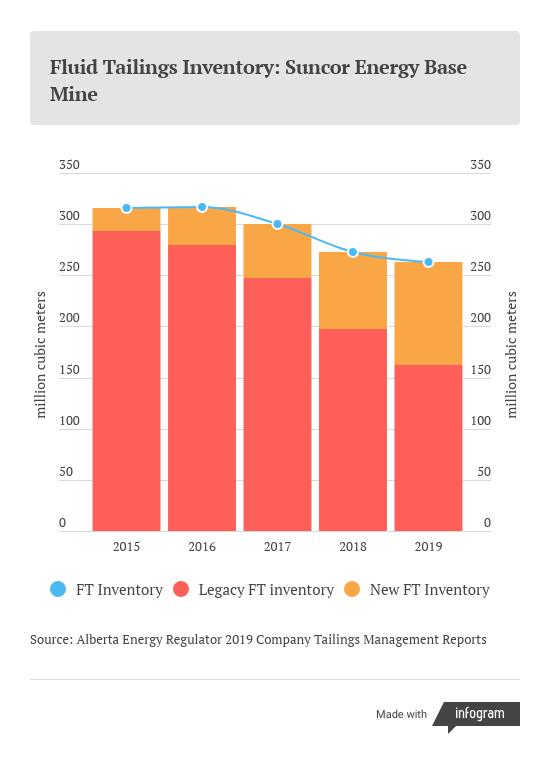

According to AER data, between 2015 and 2019 Suncor reduced the fluid tailings inventory at its Base Mine by almost 17 per cent, from 316 million cubic metres to 263 million cubic metres. This has been achieved in part by reducing its “legacy” tailings, or volumes that were in storage before 2015. Suncor reduced its legacy tailings by approximately 45 per cent between 2015 and 2019, from 293 million cubic metres to 162 million cubic metres.

In its new sustainability report the company says it is able to achieve the reductions by building on its TRO approach with a process called called permanent aquatic storage structure (PASS). Suncor says that using PASS, in 2019 it was able to treat more than double the amount of tailings that it produced at the project.

“This has been a key reason why Base Plant’s untreated fluid tailings inventory is shrinking,” the company says.

BMO also singled out the successful efforts of Canadian Natural Resources, which “has proven its ability to reduce fluid tailings by approximately 50 per cent in its latest expansion at Horizon, along with approximately 14 per cent decrease in GHG emissions, using its non-segregating tailings treatment process,” Dziuba wrote.

Canadian Natural is also “on the cusp of commercializing” a technology called its In-Pit Extraction Process, which would create dry, stackable tailings and completely eliminate the need for fluid tailings, he said.

For now, industry-wide tailings volumes continue to grow, but at a slower pace than expected. As of 2019, oil sands producers had regulatory approval to have 1.4 billion cubic metres of tailings inventory, but actually had approximately 1.27 billion cubic metres of tailings inventory, or about 10 per cent less than expected.

The future

COSIA’s Jickling says that industry is working both on enhancing and optimizing existing technologies and developing new approaches to reduce or even eliminate the production of tailings.

This includes water capping, which is expected to play a key role in the post-reclamation oil sands landscape. The approach has been used successfully in various sectors of the mining industry globally but is not yet considered commercial in the oil sands. There are currently two oil sands demonstration pit lakes: Syncrude’s Base Mine Lake, which was commissioned in 2012, and Suncor’s Lake Miwasin, which was commissioned in 2018 and is being used to validate the company’s PASS process.

The AER’s current tailings rules include a commitment for the Alberta government to develop direction for water-capping; once this direction is received, a regulatory approach specific to water-capped tailings will be developed. This has not yet occurred.

Another major future advancement for dealing with oil sands tailings would be the ability for producers to release treated process-affected water back into the Athabasca River.

There is currently zero release of treated process-affected water allowed back into the river. Based in part on analysis of a new Syncrude technology pilot as it goes forward, the governments of Alberta and Canada are developing regulations to allow for process water release, with 2023 previously set as the deadline for those rules.