While the world grapples with the Coronavirus pandemic and an economic downturn, anti-energy activists have spotted an opportunity: to kill off Canada’s oil and gas industry—the one that provides hundreds of thousands of jobs and hundreds of billions of dollars in tax revenues to governments.

The anti-oil and gas activists are busily making three claims to that end: That the oil and gas industry is massively subsidized (some claim the figure is over $3 billion annually); that fossil fuel extraction should not continue in Canada given carbon emissions from oil and gas; and that the sector is destined to die.

Let’s examine each assertion in turn.

In 2011, economists Jack Mintz and Ken Mackenzie examined the faulty assumptions behind the “billions” figure, which originated with a Winnipeg think tank but which were taken up by others including the International Monetary Fund.

Mintz and Mackenzie found four flaws including using a subsidy definition designed for a different purpose and inappropriately adding individual tax expenditures and royalty relief items up without accounting for critical interactions. In 2014, the Montreal Economic Institute found actual energy sector subsidies amounted to just $71 million. In 2017, when one of us wrote a study on subsidies, scouring Alberta and Ontario disbursements and also the federal department of Natural Resource Canada, it turned out most subsidies to energy companies were for green energy projects.

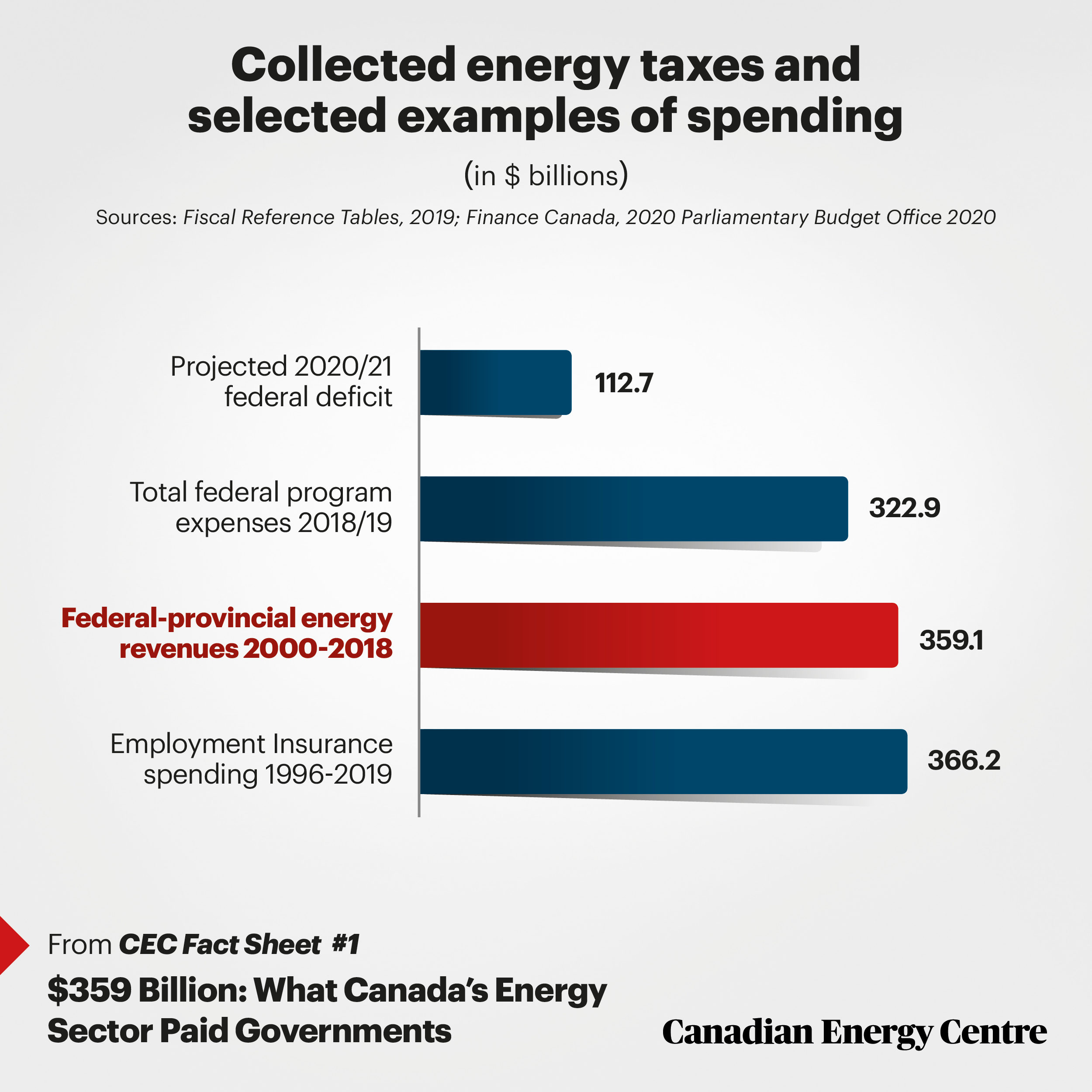

Let’s flip this over now to the taxes actually paid by the energy sector. According to Statistics Canada data, between 2000 and 2018, the energy industry paid $359 billion in corporate taxes, royalties and other taxes to provincial and federal governments.

That $359 billion figure is conservative: It does not include personal income taxes from hundreds of thousands employed in energy industry; any rents and royalties paid between 2000 and 2007 (omitted due to a change in Statistics Canada reporting); property and other taxes paid to municipalities; and payments to First Nations governments.

To put that $359 billion in perspective, the federal government paid out $366 billion in employment insurance between 1996 and 2018 in total. Those who think Canada can live without the oil and gas sector are engaged in magical thinking on government revenues and much else.

That oil and gas activity emits carbon emissions is accurate. However, those who wish to kill off Canada’s oil and gas sector too easily omit critical context: Worldwide trends mean that oil and gas consumption and such emissions will continue even if Canada’s energy industry disappears.

Consider natural gas trends. Between 2000 to 2017, the U.S. Energy Administration noted that worldwide natural gas consumption soared by 52 per cent and it forecasts another 50 per cent rise by 2050. However, here’s the problem: Canada sat out that boom in natural gas exports in while competitors soaked up the new investment, jobs and incomes.

Thus by 2017, Canadian natural gas exports relative to 2000 were down by 17 per cent. Meanwhile, Canada’s main competitors were setting record export levels in 2017 relative to 2000: Russia (up 13 per cent); Norway (up 146 per cent); Australia (up 562); Qatar (up 801 per cent) and the United States, where natural gas exports soared by 1200 per cent.

The same holds true for oil though less dramatically. Consider investment in Canada’s upstream oil and gas sector: Canada has steadily lost global market share since 2011, falling to seven per cent from in 2017 from 11 per cent in 2011. Meanwhile U.S. market share of global upstream oil and gas investment grew to 35 per cent by 2017 from 28 per cent in 2011.

Thus, while other countries carved out competitive advantages, Canada’s potential was hamstrung. That came care of activists, a few recalcitrant politicians, and more than a few investment gurus who believe — against all empirical evidence according to Bill Gates and energy expert Vaclav Smil — that the world can do without the industrial economy powered by oil and gas.

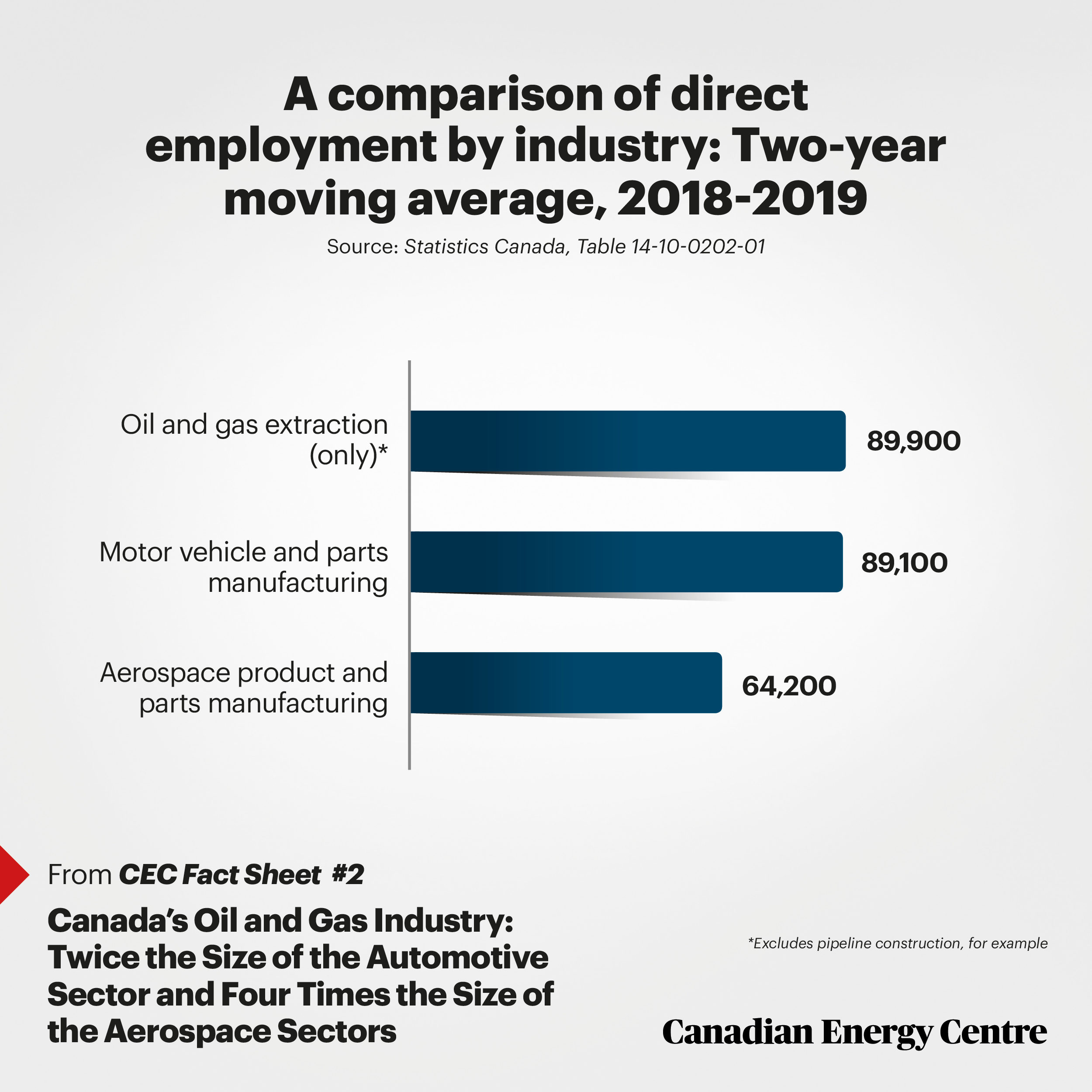

Lastly, consider another measurement of the importance of oil and gas to Canada: Jobs. Looking at just oil and gas extraction (i.e., excluding pipelines and other energy activity), employment was 89,900 in 2018. Compare that to employment in the automotive and aerospace sectors at 89,100 and 64,200 respectively. (A broad measurement from Natural Resources Canada found that in 2018, the energy sector directly employed more than 269,000 Canadians.)

The short-term outlook for oil and gas has obviously weakened because of the Coronavirus. However, demand for both products will one day resume their upward trajectory, just as they did after the 2008/09 financial crisis.

The only question is if Canada will have an energy sector or if the activists will succeed in using the current downturn to get what they wanted: The death of one of Canada’s largest, best-paying industries which benefits everyone from First Nations to blue-collar workers to government coffers.