The New York Times published an article on Wednesday describing what it called “a flood of banks, pension funds and global investment houses starting to pull away from fossil-fuel investments,” particularly in Alberta. While it is true that some banks and insurers have made the decision to divest from oil and gas projects, the article makes many statements that are misleading and need to be addressed.

“Financial institutions worldwide are coming under growing pressure from shareholders to pull money from high-emitting industries.”

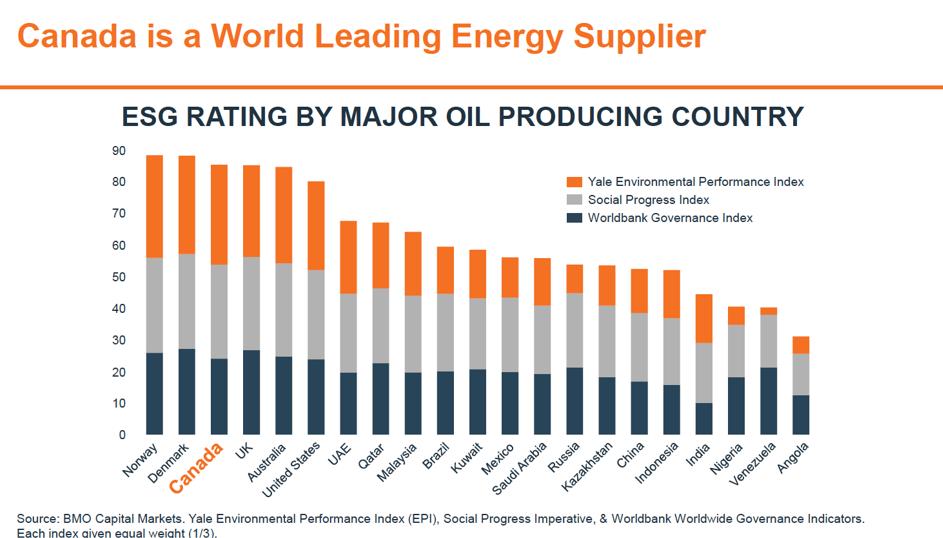

Misleading. The major trend in responsible investing is currently focused on emissions alone, but ESG is more than the environment. Investors should look holistically at overall environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance.

ESG includes environmental metrics like GHGs and water use, as well as indicators like worker safety, community investment, representation of women, Indigenous people and visible minorities, and board diversity. Canada’s status as a global ESG leader continues while its oil producers continue work to improve environmental performance.

Consider the chart below, which was included in Alberta midstream company Keyera’s 2019 investor day presentation. It compiles three performance indexes (Yale Environmental Performance, Social Progress Imperative, and World Bank Governance) to score Canada’s overall ESG performance against other oil producing countries. Canada ranks third, after Norway and Denmark.

“Oil sands extraction leads to about 70 percent more greenhouse gas per unit of energy on average than the global mean”

Misleading. This reference to research published in the journal Science in 2018 – using data from 2015 – does not provide a full picture of GHG impacts. This is primarily because it only considers what the industry calls “upstream” operations, or the activities that happen before the oil reaches the refinery inlet. But most emissions – 70 to 80 per cent – happen well after this, at the point of combustion by the consumer.

A 2014 study by IHS Markit using 2012 data ranked average full-cycle GHG emissions from Canada’s oil sands fourth highest compared to other jurisdictions including Venezuela, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia. But upstream oil sands emissions intensity is trending downward, which IHS expects will contribute to overall life-cycle reductions.

Thanks to new technologies and efficiencies, analysts now expect that by 2030, the GHG intensity of oil sands extraction could be 16–23 per cent below 2017 levels—more than one-third less than in 2009. IHS says that on a full life-cycle basis, these upstream intensities would place more oil sands projects within 2—7 per cent of the average crude oil refined in the United States.

“The world’s appetite for the most polluting fossil fuels is fading”

Wrong. The world’s appetite for fossil fuels continues to grow.

Even in the most aggressive decarbonization scenario outlined by the IEA, oil demand is expected to be 67 million barrels per day by 2040 which, despite being a reduction of approximately 33 million barrels per day from today, will still require substantial investment. The IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario, or the more likely case, sees oil demand increase to 106 million barrels per day over the same period.

There is substantial global demand for Canadian heavy oil, particularly in the massive U.S. Gulf Coast refining cluster, where many refineries are specifically designed to process this more complicated product.

Supply from other heavy oil producing jurisdictions that supply the U.S. Gulf Coast is in decline. As ARC Energy Research Institute reports, U.S. sanctions against Venezuela, including oil, have helped create a “strong pull” for Canadian oil in the U.S. Gulf Coast market. But Canadian producers are challenged to capitalize fully on this opportunity without expanded pipeline access.

Royal Bank of Canada CEO David McKay observed earlier this year that fossil fuels are required in the energy mix moving forward.

“We have to invest. Otherwise you’re going to see US$150 oil prices-plus and that’s more destabilizing to our global economy and slower on growth than you would expect.”

Government leaders also know that Canadian oil and gas will be necessary moving forward. As Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland said recently, “What I would say is my dad could not live or get around without a pick-up truck, and his combines need to run on fossil fuel…even if all Canadians ceased emitting carbon we wouldn’t move the dial. A big part of our task needs to be leading the multilateral challenge.”

Moody’s downgrade of Alberta

The Times article correctly stated that Moody’s downgraded Alberta’s credit rating in December 2019, but misleadingly implied this is largely because of the environmental impact of oil production in the province.

Moody’s did state that Alberta’s environmental risk is high, but that’s not the primary driver of its downgrade. The company said Alberta “remains pressured by a lack of sufficient pipeline capacity to transport oil efficiently, with no near-term expectation of a significant rebound in oil-related investments.”

Moody’s added that a sustained improvement in the outlook for the energy sector resulting in increased revenue potential for the province could lead to upward pressure on the rating.

“What you get is, you get a headline”

The Times quoted Michael Sabia, chief executive for the Caisse de Dépôt et Placement du Quebec, as saying the pension fund continues to invest in oil sands companies while pushing the companies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“What does divestment get you? What you get is, you get a headline,” Sabia said. “But you haven’t done anything really to direct your organization to be a positive contributor to the energy transition that the world has to go through.”