A steady stream of more than 450 oil tankers calls at ports in Eastern and Atlantic Canada every year, drawing little public attention.

That’s in part due to the industry’s safety record in the region, where accidents involving tankers are rare.

The most recent serious pollution incident from an oil tanker took place in Nova Scotia more than 45 years ago, and the last recorded minor spill from a tanker occurred 25 years ago, following a grounding incident in Labrador.

“Marine shipping as a whole is extraordinarily safe when you look at nautical miles travelled versus incidents,” said Meghan Mathieson, director of strategy and engagement for Clear Seas, an independent not-for-profit that studies marine shipping issues.

“In Canada, shipping is much safer than your morning commute driving in a vehicle. Of the spills that do occur, most come from fuel from pleasure boats or fishing vessels,” she said.

“People should not conflate debates about the pros and cons of fossil fuel production with marine safety. Is it safe to ship oil and gas in Canada? Yes, it is.”

Where tanker traffic occurs

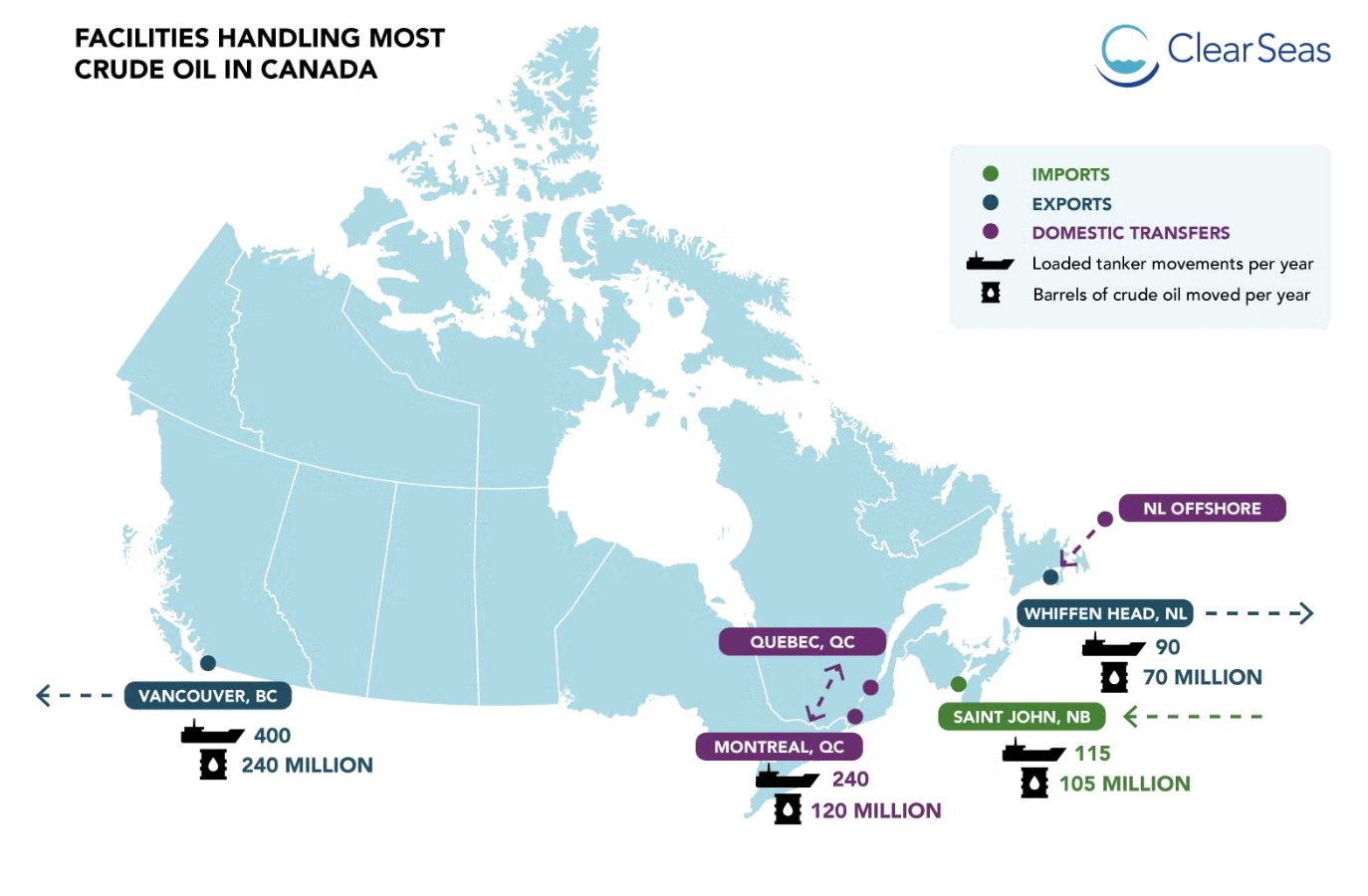

Prior to the 2024 completion of the Trans Mountain expansion, about 85 per cent of oil tanker traffic in Canadian waters took place in Atlantic Canada, according to Clear Seas.

The increase in tanker traffic off the B.C. coast has shifted the overall balance to 58 per cent of movements on the West Coast and 42 per cent on the East Coast.

In Atlantic Canada, this is divided between Saint John, NB, which sees about 115 tankers annually importing crude oil, and the Whiffen Head facility in Newfoundland, where 90 tankers are loaded for export every year.

There are also an estimated 240 shuttle tanker transits annually along the St. Lawrence Seaway in Quebec, moving oil between a storage facility in Montreal and a refining facility in Lévis.

Mathieson says there is greater familiarity with oil tankers in Atlantic Canada than in other areas.

“They have been used to seeing tankers carry oil for a lot longer in that region. But there’s a cultural component as well. Wherever you are in Atlantic Canada, you are not that far from the ocean,” she said.

“A lot more people work in the marine sector, such as fishing and offshore oil, than other parts of the country, or they know people who do. They are on the water more, so they may be more familiar with the advancements made by the industry to make it safer.”

How tanker safety has evolved

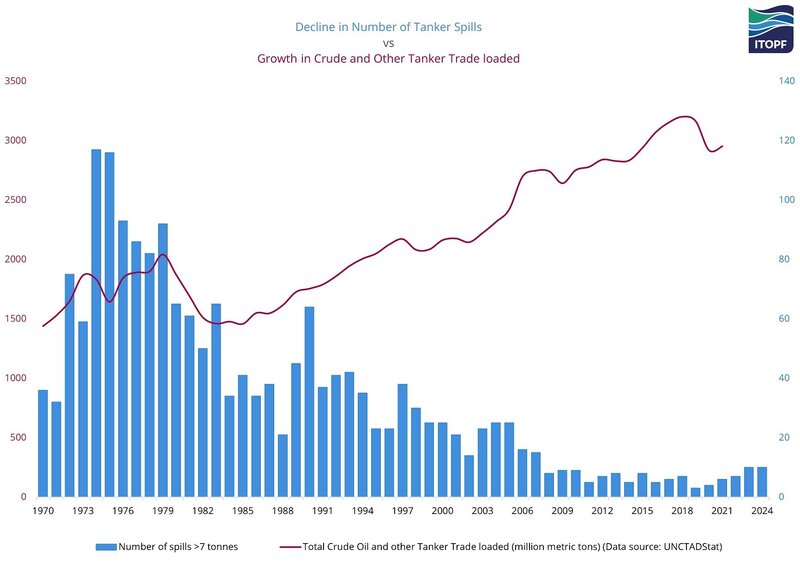

Many of those improvements came in the wake of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska’s Prince William Sound.

“Catastrophic incidents tend to stay in people’s minds when discussing marine safety, but so much has changed in the industry in terms of standards and procedures since then,” Mathieson said.

“Today’s tankers are designed to be safer—they have double hulls and reinforced attachment points for towing equipment. And the procedures and protocols have advanced just as much, from having local pilots guide them into port to inspections by Transport Canada and certified response organizations for spill clean-up.”

Spill response organizations on both coasts

Eastern Canada Response Corporation (ECRC) is responsible for responding to spills throughout Atlantic Canada as well as the Great Lakes, Quebec, and St. Lawrence Seaway.

ECRC is the eastern counterpart to the Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC), which is responsible for protecting all 27,000 kilometres of Canada’s western coastline.

In anticipation of increased tanker traffic from the Trans Mountain expansion, WCMRC completed Canada’s largest-ever expansion of marine oil spill response capacity, doubling its capabilities with new vessels and response bases.

ECMRC’s area of response runs from the Alberta/B.C. border to offshore Newfoundland and from the U.S. border to the 60th parallel.

Part of the marine community

“We have six response centres located throughout the area that face different challenges based on climate and other factors,” said Michael Kean, manager for the ECRC’s Dartmouth Response Centre, which covers parts of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia as well as the Northumberland Strait and Cabot Strait shipping areas.

“Some of those areas will ice over for parts of the year, as an example, while our region remains ice free. But regardless of the different challenges, we are training around the year so we are ready.”

The unaltered reproduction of this content is free of charge with attribution to the Canadian Energy Centre.