In the heart of Alberta’s oil sands region, a lake sits next to Suncor Energy’s Mildred Lake operation.

On the surface, it looks like one of the countless natural lakes dotting the boreal forest north of Fort McMurray. But several metres below, it tells a different story.

Base Mine Lake is not a natural lake—it’s a demonstration pit lake at one of the industry’s oldest mines.

Once a tailings pond, Base Mine Lake was capped with water in 2012 and is now undergoing reclamation, drawing on decades of innovation to restore the land and water affected by development.

“Tailings ponds aren’t meant to be a permanent part of our closure landscapes,” said Rodney Guest, Suncor’s senior development advisor, mine water closure.

“We’re investing significant resources to advance tailings treatment technologies in support of land and aquatic reclamation to meet our commitments.”

Those commitments include fully reclaiming mine sites, including tailings facilities, and returning the land to Albertans and local communities, he said.

Pit lakes: widely used around the world

Pit lakes are a common mine reclamation and closure practice used worldwide.

According to the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), a pit lake is basically any lake formed within a former mine pit.

Over time, as the site stabilizes, these lakes generally come to look and function much like natural lakes.

Thousands of examples exist globally, particularly in coal and hard-rock mining operations such as gold and copper, CAPP says.

Helping address oil sands tailings

Even as the oil sands sector has reduced its freshwater use per barrel by nearly one-third since 2013, the total volume of fluid tailings has reached about 1.4 billion cubic metres, reflecting continued production growth.

Aquatic reclamation techniques like pit lakes are helping address the tailings challenge.

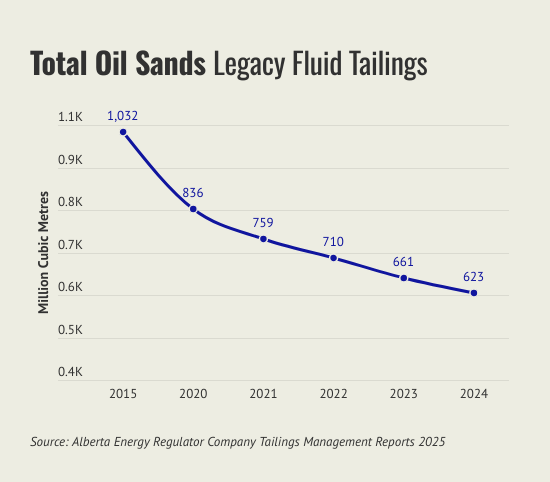

This is evident in the reduction of “legacy tailings,” or tailings placed in storage before 2015.

Since 2015, the volume of legacy tailings across Alberta’s oil sands has fallen by 40 per cent, according to Alberta Energy Regulator data.

Base Mine Lake has contributed to this reduction, which overall is helped by water-capped tailings and permanent aquatic storage structure (PASS) technology.

How water-capped tailings technology works

Oil sands tailings are a mixture of fine clay, water, sand, and residual bitumen left over from the bitumen extraction process.

Traditionally stored in large ponds, these liquid tailings settle very slowly—a process that can take decades. Water-capped tailings technology provides a more controlled solution.

In this approach, a layer of water is placed over tailings within a mined-out pit, forming a pit lake.

The water cap isolates the tailings from the surface environment while promoting the development of a natural aquatic ecosystem.

Supported by long-term research

Numerous pit lakes, with and without tailings, are proposed or planned for the oil sands region.

Each is designed to integrate into the final reclaimed landscape, supporting sustainable water management and creating new habitats for aquatic and terrestrial life.

Long-term research and monitoring at several sites—some dating back to the 1980s—has shown that water-capped tailings can be effective.

Bacteria quickly break down many compounds within the tailings, while the solids settle naturally within weeks. The water layer above largely prevents tailings sediments from migrating back to the surface.

Base Mine Lake performance

At Base Mine Lake, for example, a water cap currently between 10 and 13 metres covers the tailings. Ongoing research and monitoring show it’s performing as expected, Guest said.

“The tailings remain contained at the bottom and don’t mix with the water,” he said.

“Water quality continues to improve, diverse habitats are forming, and typical boreal lake life including insects, invertebrates, plants and mammals are present in and around the demonstration watershed.”

While the lake doesn’t currently discharge to the environment, the long-term plan is for its water to eventually integrate into the regional watershed.

Prior to release, water will be monitored and tested to ensure it meets regulated water quality guidelines, Guest said.

In the meantime, Suncor adds fresh water and withdraws water for use in its mine operations.

PASS technology demonstration

Suncor is implementing permanent aquatic storage structure (PASS) technology at a demonstration site that includes Lake Miwasin, a 10-metre-deep lake with a five-metre water cap.

PASS uses common treatment agents to help tailings settle and release water more quickly. The process speeds up consolidation and helps improve overall water quality.

The company says early results are promising, showing expected improvements in water quality and the re-establishment of vegetation.

Insights from local Indigenous communities have helped refine techniques, including influencing landform design and identifying culturally important plants and trees.

Confidence in pit lakes

“Results from Base Mine Lake and Lake Miwasin give us the confidence that pit lakes are a safe and integral component of our planned closure landscape,” Guest said.

The transition to a fully reclaimed boreal landscape in Alberta’s oil sands will take time.

Most of the reclaimed area will consist of forests and wetlands, with pit lakes expected to account for less than 10 per cent.

The unaltered reproduction of this content is free of charge with attribution to the Canadian Energy Centre.